“I Felt Like I Had to Be Perfect in Every Way”

Despite recent progress, many autistic people’s unique issues around mental health and eating disorders continue to be misunderstood or dismissed outright. As the number of people being identified and diagnosed with autism increases, it is vital that both professionals and recovery advocates include autistic voices in the conversation about body image and eating disorders.

I had the chance to speak with Lindsey Nebeker, an autism advocate and a featured subject in the documentary film Autism in Love, about her personal struggle with an eating disorder. Read on to learn more about her autism diagnosis, personal struggle with and recovery from anorexia, and how others can better support the autistic community.

Diana Denza: You were diagnosed with autism at two years old, but there are a lot of women who are diagnosed later on in life. What was it like to be diagnosed young and how did that impact you?

Lindsey Nebeker: Growing up, I knew of and was surrounded by people with disabilities, including autism. Hearing stories of colleagues and people I got to meet who were diagnosed later in life, I didn’t really get to know those people until I became an adult. So I was around people who were diagnosed much younger, and I can only speak from my own personal experience of being diagnosed very young and I think there were a couple of reasons why this was. First, my family was very lucky to have access to the resources to get me a formal diagnosis. Also, my characteristics were more profound when I was younger.

Lindsey Nebeker: Growing up, I knew of and was surrounded by people with disabilities, including autism. Hearing stories of colleagues and people I got to meet who were diagnosed later in life, I didn’t really get to know those people until I became an adult. So I was around people who were diagnosed much younger, and I can only speak from my own personal experience of being diagnosed very young and I think there were a couple of reasons why this was. First, my family was very lucky to have access to the resources to get me a formal diagnosis. Also, my characteristics were more profound when I was younger.

For one, I wasn’t speaking, and my parents weren’t sure why I wasn’t developing speech, which is why they initially took me to a psychiatrist and child psychologist who referred me to an autism specialist to give me the diagnosis. I displayed behaviors that were quite profound and were characteristic of autism. Just thinking back, while I received the diagnosis that young, I didn’t actually know about my diagnosis until I was about 10, which is when my parents broke the news to me.

I knew about autism at a much younger age, though, because I have a younger brother who was also diagnosed, but his autism affects him more intensely. For several years, I knew about autism without knowing I had it myself. But both my brother and I did get involved in early intervention shortly after we were diagnosed. I did a variety of different early intervention programs. I worked with an occupational therapist and a speech language pathologist. I started to speak at around age four, and then I was able to transition from special education classrooms to fully-inclusive, mainstream classrooms by first grade.

DD: How did your eating disorder develop and did autism play a role in the development of it?

LN: When I hear about other colleagues in the community who are on the spectrum and have developed eating disorders, I do hear that it comes from things like sensory issues, black-and-white thinking, and counting calories, and so forth. I can tell you that I was a really picky eater as a child, but it wasn’t actually severe enough to trigger a clinical eating disorder. Actually, for the first 20 years of my life, I struggled with my weight in that I was technically overweight and I was struggling with that insecurity, especially when going through grade school, junior high school, and high school – those are very insecure times – but I didn’t ever think I’d develop an eating disorder.

And then at around 20 or 21, I wanted to change, and I did, but I didn’t know how to stop it. I just couldn’t control it. And so, it led me to where I was battling with a very severe case of anorexia. I voluntarily took a medical leave of absence from school to focus on treatment. I did outpatient treatment, so I lived at home with my dad, worked full-time, and participated in treatment to work on my recovery. I was able to go back to school the next semester and complete my degree, but after that, I continued to struggle, not with anorexia, but with ED-NOS [Editor’s note: now recognized as OSFED] off and on for the next 12 years.

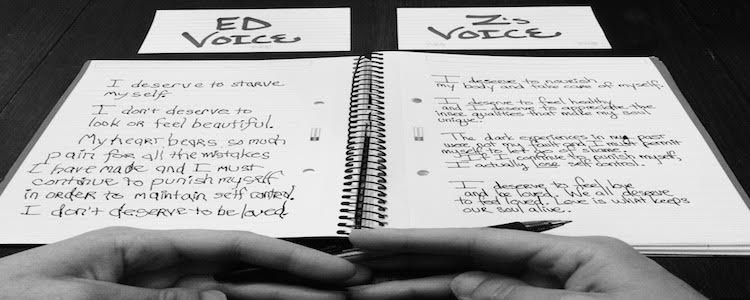

It wasn’t until I went back to treatment two years ago that I finally made major progress in my recovery in that I started eating normally again for the first time in so long. Through this journey, I had been trying to figure out what triggered it, because when I was in recovery from anorexia, I was interested in learning whether or not my autism had contributed to it. In some aspects, I feel like it did, but not as a trigger. But I think my autistic characteristics exacerbated my eating disordered behavior, as well as the length of time I battled these behaviors and my recovery process. Things like counting calories, for example, or maintaining self-control or a sense of routine. That has always been a part of my autistic identity, that need for self-control, because we feel like we’re in a world we feel alien to. For some of us, that can turn into the form of an eating disorder.

I know that when I was going through early intervention as a child, I had to learn certain motor skills, like gripping onto utensils, and I know when I became very sick with my anorexia, I stopped remembering how to grip utensils properly. Part of my recovery involved redeveloping my motor skills.

DD: What are some other things you felt triggered eating disordered behaviors in you?

LN: It took a while to figure out, but I’m convinced that what actually triggered the eating disordered behaviors was my responses to the trauma that I experienced in high school. I went to boarding school for my last years of high school, and I experienced a lot of different traumatic events, one of them being that I was sexually abused by one of my high school teachers, so I was able to do a lot of piecing together and thinking and realizing that those were such traumatic experiences that it took me a long time to build the courage to confront my past.

What happened, I believe, is that when we experience something traumatic, or when we face something that has torn apart our lives in some way, even if we’re not ready to confront it ourselves head-on and feels those emotions, it somehow still comes out. So I feel that engaging in my eating disorder was a way that the truth of the emotions was coming out.

DD: Is there anything you wished your loved ones or treatment professionals would have done differently when you were struggling with an eating disorder?

LN: I am grateful for what I was able to achieve out of recovery, and I’m incredibly grateful, so there were ultimately many positives that came out. But I do wish there had been more patience, and I also felt like there was a lot of misunderstanding about why I was struggling with my eating disorder. I think a lot of people seemed to assume that it was due to pressure with comparing myself to women on magazine covers or something like that and it really had nothing to do with that.

Also, one of the most frustrating things, in my experience, was that I knew there was a problem for a while before it got really bad, and I was trying to communicate to my parents and my friends that I was really worried, and that I couldn’t control it and needed to get help. And they would keep saying things like, “Well, if you are able to just stop now and maintain yourself, you’ll be fine.” I don’t think they took my concerns as seriously as I wish they did.

I feel that whenever I try to communicate that I need help or support, that it doesn’t really get taken seriously until it’s almost too late. And when I started treatment, I of course was faced with loved ones who were very concerned and would be very angry and get heated, and that didn’t help me. What I needed were people to be patient and to practice compassion, and to still offer me unconditional positive regard.

DD: Do you think some people had a lack of awareness or knowledge of eating disorders or was there a communication difference due to autism that prevented them from understanding how serious your struggle was?

LN: I think it’s actually a couple of different things. One of those things is a communication barrier. Even though I have been able to develop speech and get by in spoken and written communication, I still am not very good at being explicitly direct when I need to be. I’m still working on communicating my needs clearly and identifying when I need help, but the problem is, when I communicate when I need help and support, I assume people understand me. But in the end, when we reassess the situation, what I hear from the other side is that they didn’t really understand what I was trying to communicate to them. I’ve come to the conclusion that perhaps, the way I communicate is quite indirect, or I’m not clear enough so that they understand the scope of why I need help.

A little over a year ago, I survived a suicide attempt. Recently, I opened up about it publicly and told my parents for the very first time, and the conversation with my dad – he said that this was actually a really insightful learning experience for him to learn about this because they originally believed the incident was an accident. So when I broke the news to them that it wasn’t an accident, my father admitted that whenever I went to him with something throughout my life, he might have taken the autism and used that as the excuse, almost separating the autism from the real-life issues we experience as humans.

Well, autistic people are human and as humans, we can experience the same things. We can experience eating disorders. We can experience mental illness. We have the capability to experience all of these similar issues that can co-exist with our disability. Perhaps, a lot of people don’t realize it yet.

DD: Some people seem to still hold a very stereotypical view of autism, and I’m glad you brought that up. I wanted to ask about Autism in Love – did you feel that you were portrayed in a fair and accurate manner in the film and did you believe it raised positive awareness for autism?

LN: I feel like it was a very complex adventure. When you see the film in itself, the three stories that are highlighted and how they’re put together and the overall message, I think it was beautifully done. I think it was something that definitely shifted a paradigm, but it was certainly not perfect. It did receive a lot of very positive responses, but it also had some criticism that it wasn’t diverse enough, which I agree with. And I feel that even though it was not perfect and there are many more steps to take in terms of diversity in the disability media, I do feel like this film really did help because it showed the message that autistic people do have the capability to love and do want to be loved, whether it’s romantic or not romantic.

During the filming, we were treated very well, and the support that we did receive after the film was really encouraging and it feels good to give back in some way and share our lives. After the film came out, I struggled with really understanding whether our story was real, if our lives were really real. And with the criticisms [online] that came out of it, I kind of got sucked into that, and really believed in the criticism. That put me in a downward spiral, but I don’t at all regret doing it.

DD: Did participating in the film or receiving negative comments online trigger any body image insecurities?

LN: It did in the sense that we had been in the public eye off and on for the past eight years. Even though comments about my body had never come up, I had grown up trying to be as perfect as possible. I was trying to achieve perfection because I didn’t want to be viewed as less than, as just a person with a disability. And so I felt like I had to be perfect in every way, and to not present myself as vulnerable. I felt like appearance had to play a role in that for me.

In the last three months of filming, I did go through a phase of compulsive exercise and purging because I was concerned about how I would appear on screen. I had concerns about how I was perceived by other people, but it’s due to not wanting to be seen as vulnerable, which is how many people with disabilities are perceived to be.

DD: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share?

LN: I guess what I would say when it comes to recovery and how people can support autistic people with eating disorders is just like with any other areas of progress, whether it’s speech or communication, patience and validation are key to progress and recovery. And this focus on routine and self-control, don’t try to eliminate it or take it away, but try to redirect it to healthier coping mechanisms. Don’t make assumptions: treat us as human – we are people – but also treat us gently, with kindness and unconditional positive regard.

Note on terminology: Lindsey uses “person with autism” and “autistic” interchangeably. For more information on person-first vs. identity-first language, please click here.

For more on autism and eating disorders, check out a recap of last month’s Autism Acceptance Month #NEDAchat.